By Jacquie Gilson, Doctor of Social Sciences

Yorke Edwards has always been an inspiration to me. I recall excitedly reading his book The Land Speaks: Organizing and running an interpretation system when it came out in 1979. That is the year I started studying interpretation at university and his thin, but jam-packed book, was introduced to us. I devoured this “required” reading and felt an immediate connection with Yorke as I read it. I too was a nature-loving urbanite from Toronto who wanted to break the bonds of the city and work in the natural world. Like Yorke, I went on to spend my entire career working in the interpretation profession within various parks systems. Yorke was a leader in the new field of interpretation in Canada. He laid the groundwork for us to follow, and when I proudly refer to interpretation as a “profession,” I now realize that I have Yorke to thank.

The Object’s the Thing is a collection of his writings from throughout his long career. I am grateful to those who saved these writings and chose to make them available to all. I love the title, as it hints at deeper ideas, and I waited patiently until the section in which the meaning was revealed (it’s on page 264, if you can’t wait.). I did the math and discovered that The Land Speaks and The Object’s the Thing (the original piece of writing under that name) were written around the same time, when he was 55 and at the peak of his career. Both spoke to me because they encourage taking a deeper look at our profession. It was worth the wait and that particular piece gave me much food for thought.

The book is chronologically divided into three sections, based on his places of employment over the 25 years from 1962-1987. I enjoyed reading his writings in this order and I pictured him gaining confidence and becoming more and more enthused about the idea of interpretation as the years went by

As a child, Yorke spent as much time as possible exploring nature in the outdoors and at the Royal Ontario Museum’s collections in Toronto. This led him to a lifelong belief that for people to connect to nature they needed to experience the real thing. His love of nature shines through in his writings, as does his concern that modern people are disconnected from it.

As a young adult, he moved to BC to study and then to work for the Parks Branch. His writings in this first section reflect his youth and enthusiasm for parks and this new idea of interpretation. I enjoyed reading his brief annual reports to management, in which he highlighted the growth of the programs and the increasing visitor interest in the nature houses. I loved his reference to “spot talks” as informal interpretation provided where and when people were available. The terms used to describe these interpretive moments have changed over the years, and we have called them point duty, point stations, pop ups, and my favourite, activity stations.

Yorke then moved to Ottawa to work for the Canadian Wildlife Service, planning a series of nature centres to be developed across the country and aimed at helping Canadians understand conservation. His writings in this section remained positive and hopeful and you can see that he is formulating his ideas for what makes interpretation successful. He seems to struggle with the idea of developing centres, since they take people indoors, when, in his opinion, they need to be in the outdoors, i.e., in the real thing. Reading this section was difficult for me, knowing that the conservation program and centres soon received major cutbacks, something he was blissfully unaware of in his writings.

His career aspirations then took him back to BC, where he worked at the BC Provincial Museum as assistant director and director until his retirement in 1984. The writings in this section to me seemed to show his maturity, but also his frustrations with financial restraint and bureaucracy. Regardless of his role throughout his career, he always advocated for “inspirational public programming” as a way to connect visitors to the parks and the natural world (p. 14).

The introductory sections written by Richard Kool, Robert A. Cannings and Bob Peart helped me to put Yorke’s writing into context. It was very useful to know how his work fit into his career and the times he was in. After I finished each of Yorke’s pieces of writing, I found myself wishing that my contemporaries would weigh in and share their thoughts on the relevance of that writing for us today. I especially wanted this kind of a summary from the editors after I completed my reading of the final piece of Yorke’s writing. I guess that task falls to me as a reader; I need to make the content relevant to my work. I did go back and reread the editor’s sections after completing the book and this gave me the closure I was desiring. I suggest that you do the same; read it from front to back and then read the writings of the editors. I realize that this does not give Yorke the final say, but I think it helps to put all his writings in perspective.

Interestingly, Yorke addressed issues that we still grapple with in interpretation today. He wondered about the term “interpretation,” describing it as a dull and colourless name; something that many in the field still question. The definition he published in 1977 still guides us, and yet is cause for ongoing debate. At that time, he said, “Interpretation is attractive communication, offering concise information, given in the presence of the topic, and its goal is the revelation of significance” (p. 28.) We still haven’t come up with a better one that is more relevant to our times. Also, he was adamant that the real object needed to be present for good interpretation. This notion is now questioned and the debate continues, as we wrestle with the role of technology, exhibits, and even visitor centres, as sources of inspiration. He addressed the role of information a number of times and I sometimes found myself in disagreement with his views. At the time he was writing, sources of information were limited and the interpreter was seen as the purveyor of knowledge. I think we now have the opposite problem, with TMI (too much information) dominating our world. For today and the future, I think an interpreter’s role is to help dispel misinformation, but also to engage people in honest dialogue about topics of relevance. Information clearly has a role to play, but perhaps not as strong a place as he believed.

As someone who completed her doctoral dissertation on the concept of inspiration in interpretation, I was overjoyed to see his use of the idea of inspiration throughout his writings. At one point, he said, very simply, that interpretation “shows, orients, informs, inspires and entertains” (p. 30). Inspiration was the one of these five words that he used the most in his writings. I wholeheartedly agree with his assertation that an interpreter is an “Enthusiastic purveyor of inspiration” (p. 30) and that interpretation should inspire people to take action. I am thankful to him for his original writings, in which he was not afraid to wax poetic about such lofty subjects as inspiration. I know his work inspired me to explore inspiration.

I am pleased that I now have two books by Yorke Edwards on my bookshelf. I trust that my copy of The Object’s the Thing will be just as well loved and marked up as my copy of The Land Speaks. They both already have many tabs marking special sections and my favourite quotes. If you don’t already have it, you can access the full text of The Land Speaks here: http://parkscanadahistory.com/publications/nppac-cpaws/the-land-speaks.pdf and then you too can have both his books standing proudly next to each other in your collection.

Yorke wrote with so much enthusiasm for the nascent profession of interpretation that you cannot help but be inspired. However, he wrote during simpler times. As we face today’s challenges, we need to keep his writings in mind and let his passion inspire us. Modern interpretive professionals need to figure out how we will navigate this new world. I believe, as Yorke did, that the profession of interpretation has something to contribute towards making the world a better place. Let’s use Yorke’s enthusiasm as inspiration to keep interpretation alive and well, because, in his words, “… interpreters never can know how far the ripples travel from where they have dropped new understandings” (p. 293).

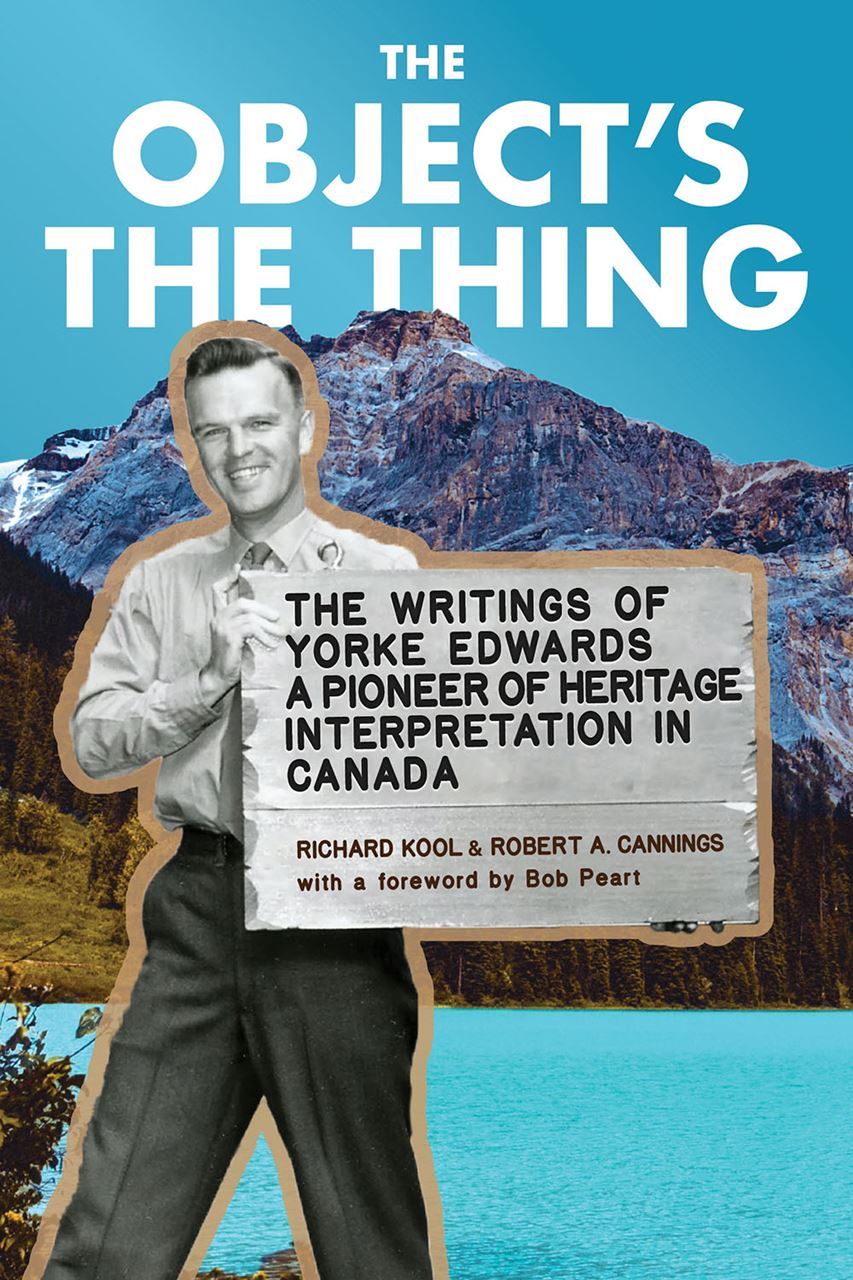

Book Review of The Object’s the Thing: The writings of Yorke Edwards a pioneer of heritage interpretation in Canada, edited by R. Kool and RA Cannings, published by Royal BC Museum, 2021.

Jacquie has been involved in interpretation, and loving it, for more than 40 years. After studying the concept of inspiration in interpretation, she received her Doctor of Social Sciences degree from Royal Roads University in 2015. Jacquie recently retired from being an Interpretation Coordinator for Parks Canada in Banff National Park and she now runs her own company, InterpActive. She focuses on interpreter training and her specialty is online training on dialogic and participatory interpretation. Check out her current offer here www.interpactive.ca. Look for her book Inspired to Inspire: Holistic Inspirational Interpretation on Amazon.ca https://www.amazon.ca/dp/B08SB3922Y